London 2012 will always have a very special place in my heart. That magical summer still seems like a dream. And even though I was involved directly for over two and a half years, I never truly imagined the impact it would have and its dramatic success. It showed off what an amazing place London is, surprised the world with the way the public and Games Makers were so welcoming and, frankly, un-British and how to plan and execute such a large scale event and manage to leave a positive legacy.

I’m sure much will continue to be made of the sporting legacy and whether participation in sport has simply remained stagnant. I guess only time will tell whether the phenomenal medal haul by Team GB and Paralympics GB has really inspired a generation. There is, without doubt, an increased interest in volunteering, which has been further enhanced by this year’s Tour de France and Glasgow’s Clydesiders.

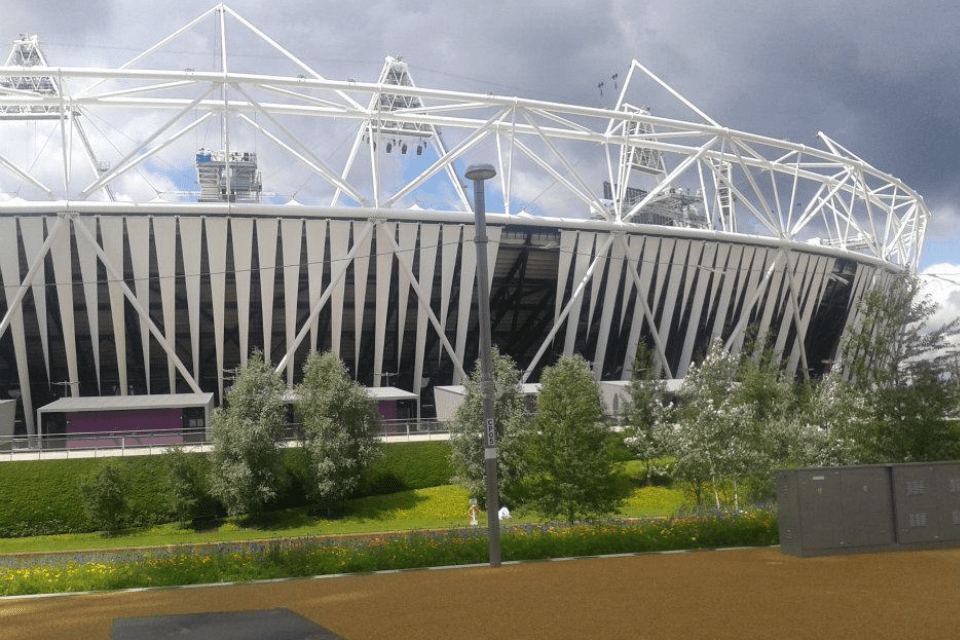

The other success of the Games is evident for all to see. If you’ve not done so, I urge you to take a train to Stratford station, walk briskly through the wind tunnel alongside Westfield and spend some time in one of the world’s few fully functioning, living, breathing Olympic Parks. The wait for the transformation work after that heady summer was well worth it. We are blessed with a spectacular, free to attend, attraction that is brilliantly served with a plethora of public transport links. I’m not a big shopper, but the Westfield complex is impressive in its own right and handy if you are looking to refuel during your visit.

The now iconic, state of the art venues that have finished their transformation from Games-mode and are now all open to the public. The Velodrome remains a magnet for visitors with its distinctive Pringle-shaped roof, timber cladding and the bizarrely inviting polished concrete interior. The Copper Box, whose simple but perfectly descriptive name mirrors its simple, yet attractive design. Then we have the butterfly that underwent a reverse metamorphosis and lost her wings to become the stunning beauty of an Aquatics Centre that Zaha Hadid always intended her to be.

Most importantly, these glorious pieces of reborn architecture are in constant use by members of the public, who just fancy having a go in the playgrounds of their sporting heroes, local clubs and a smattering of professional athletes looking to hone their skills and further improve their performance levels.

The key difference compared with previous Olympic Parks is that a legacy was identified and designed into the build from the outset. Something that, sadly, cannot be said in the case of Athens – this summer’s 10-year anniversary photos of derelict venues a tragic sight for any lover of sport and of sensible public spending. Back at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, the media complex is becoming a new commercial hub, named Here East, and Eton Manor is now home to both Hockey and Tennis. Meanwhile, the BMX Track and the Basketball, Riverbank and Water Polo Arenas embraced the need for temporary seating. The first is now reconfigured as a less challenging track with no grandstand, with the other three all a distant, happy memory. Aside from all the success, there was one major change to the original plan – the Olympic Stadium.

When I first saw Populus’s designs for the focal point of the entire Games, I was distinctly underwhelmed by what, at first glance, seemed a very dull, functional bowl. However, as I heard more about the structure, minimal use of materials and legacy plans, I became quickly impressed and proud of what London was looking to achieve.

The fate of an Olympic Stadium in recent decades has been one of two options – remove the track and convert for other sports or try, often unsuccessfully, to remain as a multi-use venue. London’s plans rewrote the rulebook by making the upper tiers a temporary structure that could be unbolted and removed like a giant meccano set. This would leave a home for athletics with a sensible 25,000 capacity, with the scope to increase for major championships.

Where I was utterly convinced that this ingenuity was perfectly aligned with London’s apparent desire to be a different Summer Games, something also evident from the unique logo and mascots, others felt that the cost was too great to pull most of it down in order to leave a venue that would only be filled a few times each summer.

Suddenly, there was a new news story and a political push to find a tenant for the entire stadium. The disappointing thing for me and, I suspect, the architects was that plans were made specifically for a ground-breaking two-piece construction. In the blink of an eye, that had all changed. Had this been planned from the outset, tenants could have been confirmed and the design process would have been able to account for the various needs of whichever events were to take place there. Taking a decision so late in the day to look, in all reality, for a football team to become the main user immediately meant that there would have to be compromises.

As soon as the tenancy debate started, it was only ever likely that West Ham would be the main tenant and that British Athletics would have to be given access during the summer months. As a Spurs fan, I understood that Daniel Levy had to become involved, not because any of us wanted to move to Stratford, but that we didn’t want to see a local rival benefit from a low-cost new home. White Hart Lane is not blessed with public transport options and the local roads quickly become gridlocked before and after each match. With a plan to add 20,000 seats, the challenge of transport becomes all the more critical.

Had Spurs won the right to the Olympic Stadium site, the transport challenges would have been resolved immediately, but the plans to demolish the entire stadium and remove the track would not have sat easy with me. Whilst I am from Essex and my journey would have been eased, I’d have felt like a trespasser on West Ham’s manor. The same could be said of Leyton Orient’s claims – they are not from Newham and I’m not convinced their survival is at risk.

Reluctantly, I have to accept that West Ham’s tenancy was the next best decision once the original plans were axed. This is a one-off opportunity for a team that flatters to deceive even more than my own to make their mark. That so many people will be able to get to the Olympic Stadium within an hour gives The Hammers a chance to expand their fan-base and half a chance to even fill every seat it on a regular basis. They may need to be creative – cheap seats for children and maybe a neutrals section for the curious to come along and experience the home of London 2012 without becoming embroiled in football’s rivalries. This alone means Daniel Levy has a huge challenge to ensure Spurs don’t get left behind in the coming years.

That the lower bowl, ironically the one part that was designed to be permanent, is being reconstructed to have sliding seats that can cover the athletics track is a big positive. It’s far from perfect as the upper tier remains a long way from the pitch and it will be interesting to see this new configuration at next year’s Rugby World Cup, and to listen to the experiences of those seated up in the gods. The Stade de France works, to an extent, and does allow multiple use as a venue for team sports and athletics, which suggests this model could also succeed on this side of The English Channel.

Although it wasn’t in the original masterplan, I’m glad an option for a multi-use venue in London was found and that the legacy for athletics is retained. From a personal perspective, I also hope that Essex’s Eagles manage to get a look in with one or two T20 games. Chelmsford is a riot of noise with just 6,500 fans, so just imagine what a large crowd of Essexers might be like on a balmy summer’s evening. I, for one, can’t wait to find out.