Let me start with an ‘official’ definition of architecture. Oxford dictionaries opts for a simple “art or practice of designing and constructing buildings”. Dictionary.com expands this to “the profession of designing buildings, open areas, communities, and other artificial constructions and environments, usually with some regard to aesthetic effect.”

In my view, architecture is the design of spaces that need to be functional, optimise the use of available space, give the client what they want (even if that means helping shape their thoughts) and are sensitive to cost, but all the while having one eye on pushing convention and creating something that is aesthetically pleasing and that compliments, or even enhances, its immediate environment.

The most visible and frequently talked about pieces of architecture tend to be large towers in our main cities and aspirational homes in magazines and on TV programmes like Grand Designs. There are, of course, many other outstanding pieces of architecture, from museums and shopping centres to majestic bridges spanning valleys and rivers. In general, the examples people notice have one thing in common; they range from just the big to the utterly enormous. The other ubiquitous trend of recent times for architecture of the four-walled variety has been glass, or at least the need to make use of natural light and to give great views out from within.

Stadia and other sporting arenas offer a great opportunity for an architect to create a statement landmark building, as well as providing the owners with a way of distinguishing themselves with a place that not only works for the functional elements of an event, but that has a pull of its own that draws new people in to take a look.

Unlike many other buildings, a stadium project presents a number of very unique challenges alongside an opportunity to showcase creativity, ingenuity and to push the limits of engineering with a visionary combination that could otherwise be applied to towers, bridges or even shopping centres. The stadium provides a canvas for expression with almost limitless boundaries. Most new stadia have a vast footprint and for those needing a large capacity, height is on offer. Offices and hospitality spaces are required and the roofing allows for amazing supporting structures to span each ‘valley’ between the corners. Sliding roofs cover expanses otherwise seen only in new airport terminals. And ingenuity is called for when looking to make use of every square metre of space under the concrete seating bowl.

Together with the chance to find ways of lighting such a great space; ensuring the acoustics are optimised to keep the crowd noise within; making sure each client group has the space they need; using nature to help heat and cool as much as possible, whilst keeping the worst of the weather out and letting sunshine in, and accounting for the requirements of TV and the governing bodies of a variety of sports, the architect must always remain conscious of the need for spectator safety.

The external shell of a stadium is another opportunity in itself, with a chance to experiment with glass, and any number of materials to create an outer skin. Of course, another option is to go skeletal, and let the world see your frame, as is the case around three-quarters of Twickenham Stadium. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder and this beholder would like to see it cover up, if only to make the match-day experience a little more pleasant. As any 6 Nations match day visitor will testify, Twickenham really embraces the use of natural ventilation and cooling at its most basic level!

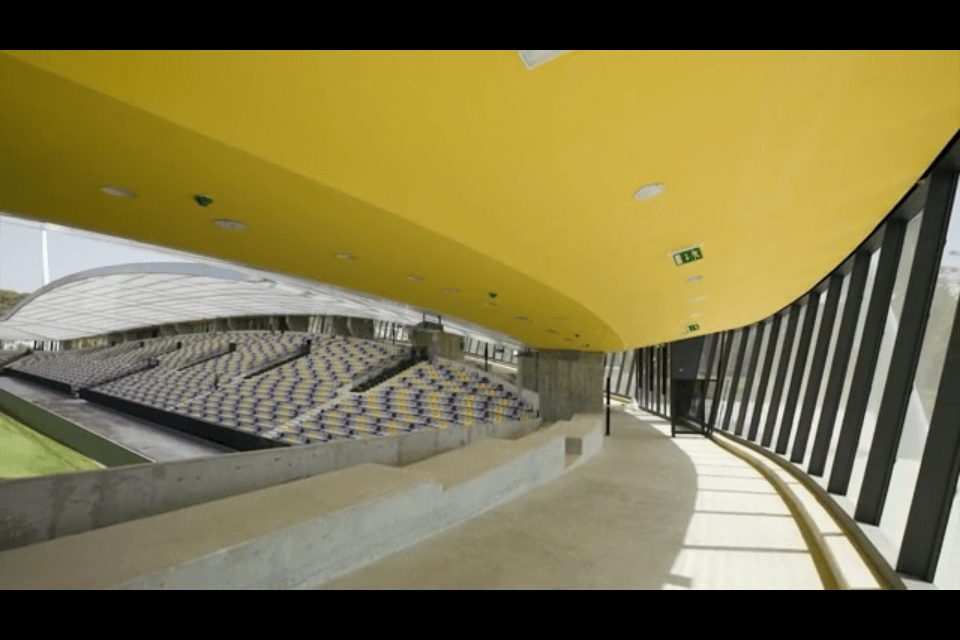

I’ve recently been fortunate enough to speak to one of the principal architects behind NK Maribor’s Ljudski Vrt stadium (that’s in Slovenia) and FC BATE’s Borisov Arena (in Belarus) to understand some of these challenges and opportunities first hand. Whilst neither stadium is all that large (both capacities of around 13,000), a number of design considerations had to be taken into account. Despite the requirements for a compact arena, the architects, OFIS, successfully created two stunning landmark buildings. The Ljudski Vrt in Maribor worked around the original arched concrete roof of the existing main stand, beautifully blending new with old in dramatic fashion. The walkways that circumnavigate the new seating bowl with their glass barrier to the outside world don’t feel they belong in a stadium, but add to the internal look and feel and give an impression of something very different to a football stadium from the outside. OFIS also considered operating costs by allowing all that daylight in at the back of the stands and designing the roof to be translucent, meaning that the floodlights also illuminate spectator areas, reducing the need for additional lighting.

Ljudski vrt. Image: Tomaz Gregoric

Ljudski vrt. Image: Tomaz Gregoric

Borisov was a different proposition; a new build, with more space available set within a pine forest on the outskirts of the town. The challenge here was to integrate a stadium with its immediate environment. Whilst the shape and look is not particularly in keeping with what you might expect in a forest, the way that the parking has been hidden amongst the trees, and the landscaping has been provided by nature, means that this unusual design doesn’t seem too out of place. Natural light and ventilation come from the spots around the aluminium skin, which are semi-transparent and vented. This skin also keeps the worst of the Belarusian weather out and enhances the atmosphere inside, which BATE’s players are said to appreciate as it makes the stadium feel full even with a lower attendance for their smaller league games.

Borisov Arena. Image: Tomaz Gregoric

Borisov Arena. Image: Tomaz Gregoric

Whilst a few architecture firms specialise in sporting venues, OFIS are not strictly stadium experts. They are brilliant ‘generalist’ architects, if such a term exists, who design a range of buildings, from chapels to apartment blocks. But, it was their first stadium design in Maribor that put them on the map, highlighting just how important a stadium project can be for an architect. Moreover, much as stadia clearly need architects, I believe architecture needs stadia as they provide such a diverse opportunity to explore and experiment with a variety of ideas, which produce buildings that vast numbers of people get the chance to enjoy.

Architecture and me

As an aside, I’ve written previously that I’ve recognised in recent years that I’d have loved to have been an architect, designing fantastic, unique stadia. I know it’s probably too late to qualify as an architect, but it is a dream that keeps coming to the surface, and it is this thought that prompted this particular article. I’ll keep writing and remain hopeful that one day I might just be able to influence the design of at least one stadium!