As a Spurs fan who has only once travelled to an away game, I had never managed to find my way to the ‘dark side’ of North London. Having some spare time over recent weeks led me to question whether any claim I may have for credibility in terms of my stadium writing could really be justified when I was refusing to take a look at such a significant specimen so close to home. Perhaps age has mellowed me, and I may finally be growing up a bit – after all, I did buy my first red car last year – so, I decided it was finally time to look past my misgivings and book up for the tour of Emirates Stadium. Still allowing me to retain the same illogical pride that would once stop me buying anything made by JVC, I didn’t part with any of my own cash directly (I have since moved away from this futile stance by purchasing phone contracts with O2 and flying with Emirates). Instead, I made use of a Red Letter Day voucher I’d been gifted, which had been waiting for the world to open up post-lockdown, to pay for the tour.

I felt somewhat uneasy walking out of Arsenal station and through the entrance to the stairs at Highbury House, reminding myself to focus on the stadium and not the club. I was quickly struck by how well such a major structure hides between the railway lines that converge just to its north. This was the first fundamental difference I noticed with the similarly sized Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, which shouts loudly and proudly about its presence for miles around. The Emirates only makes itself known publicly from the south west corner, rising up above the club shop to the wide expanses of the concourse that surrounds the whole venue; another major difference to Spurs’ roadside location.

From the outside, the stadium retains the look of a new build. This continues internally; the whole place looks in surprisingly good shape given that it opened almost 16 years ago. The general impression walking around the perimeter is that the lower level is more about functionality than trying to impress, which probably reflects the advances in expectations over the years. Trying my best to quash any biases I have, I personally prefer the expanses of glass used in Spurs’ design that rise up from ground level. However, despite no longer being the capital’s shiniest and newest place of footballing worship, Arsenal’s place holds up well.

Inside, the Directors’ lounge has a remarkably similar look and feel to that of the Emirates lounge in Dubai airport, mainly down to the dark wood that is widely used for the panelling. It’s not ultra-modern, but I’m sure it provides a sufficient sense of luxury for its guests.

The seating bowl has a pleasing uniformity, with a ring of four levels that run uninterrupted around the pitch. That being said, I am drawn more towards something with a little more variety, like the huge single-tier South Stand at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, Atléti retaining the original main stand at the Metropolitano, and the way that Brentford have shoe-horned a stadium into their available space, leading to some abstract shapes in the design of their stands and the resulting roofline.

The red seating is a bit faded in parts, but that is one of the few signs of age across the entire building. The replica clock and renaming of the southern stand as the ‘Clock End’ in homage to Highbury is a nice touch, but the clock itself looks like a cheap add-on that doesn’t give the impression of something that was considered in the original plan; this feels like a big miss. The equivalent for Spurs is the replica of its original cockerel, which had its own purpose-built prominence high above the pitch. I suspect that this is a lesson that was learned from the Emirates and is one clear advantage of following rather than leading; as was Daniel Levy’s decision to make the capacity slightly larger – very much a case of being able to say ‘mine’s bigger than yours’.

Elsewhere in the seating bowl, there are just two large screens in opposite corners. This may be enough from a practical sense, but now looks dated given the vast spaces available in each corner under the roof. Additionally, the advertising boards are fixed on the upper levels, which is one noticeable difference with the latest stadia that make full use of this digital advertising and communication capability. Much was made of Tottenham’s stands being so much closer to the pitch than at other comparable stadia (read: The Emirates), but I was surprised that this wasn’t immediately apparent; afterall, it has nothing on the experience at London Stadium, despite the determined efforts to improve the situation for Hammers fans.

My first interaction with one of the stadium team was at the museum entrance as I was trying to find the start of the tour. Here I found a fellow stadium geek who was happy to chat about the places he’d visited around the world and how much he was looking forward to the opportunity to compare his “cathedral” with mine. He was just one of a number of lovely guides I met throughout the tour. One of whom showed himself to be a far bigger man than me, as it turned out he was a fellow Spurs fan. Despite the club conflict, the chance to work in one of these iconic structures would be tough for anyone with a pull towards sport or stadia to turn down.

The self-guided tour is worth taking no matter who you support. If you have similar concerns about visiting one of your rivals, this is far from being an outlet for Arsenal’s self-congratulation. And you can easily bypass some of the more celebratory elements, especially as the museum is an optional extra that you can ignore entirely at the end of the tour, as I did. Feel free to use my line whenever asked to pose for a photo opportunity with a trophy in front of a green screen: “I don’t do trophies as a Spurs fan,” I joked. I guess this would also work for a lot of other clubs, although, I suspect I was not the first to say something along those lines.

If you do find yourself with a bit of extra time whilst in the area, the short walk from Arsenal station to Highbury will take you back to the 1930s with the well preserved Art Deco façade of the East Stand now the frontage for one of four blocks of flats that make up Highbury Stadium Square. The way that the East and West Stands have been retained and repurposed, whilst adding new buildings in place of the North Bank and Clock End, all surrounding gardens that mark the location of the pitch, is simply a work of genius that has led to one less grand old stadium being completely lost.

All in all, I had a very pleasant afternoon of geeking-out on stadia in an alien part of North London. I think the sunshine helped, but I still came away with that familiar feeling of contentment at having had the opportunity to see a different stadium up close. Most surprisingly, any of the original doubts and feelings of treachery I’d had beforehand had completely melted away.

Image: Tottenham Hotspur

Image: Tottenham Hotspur

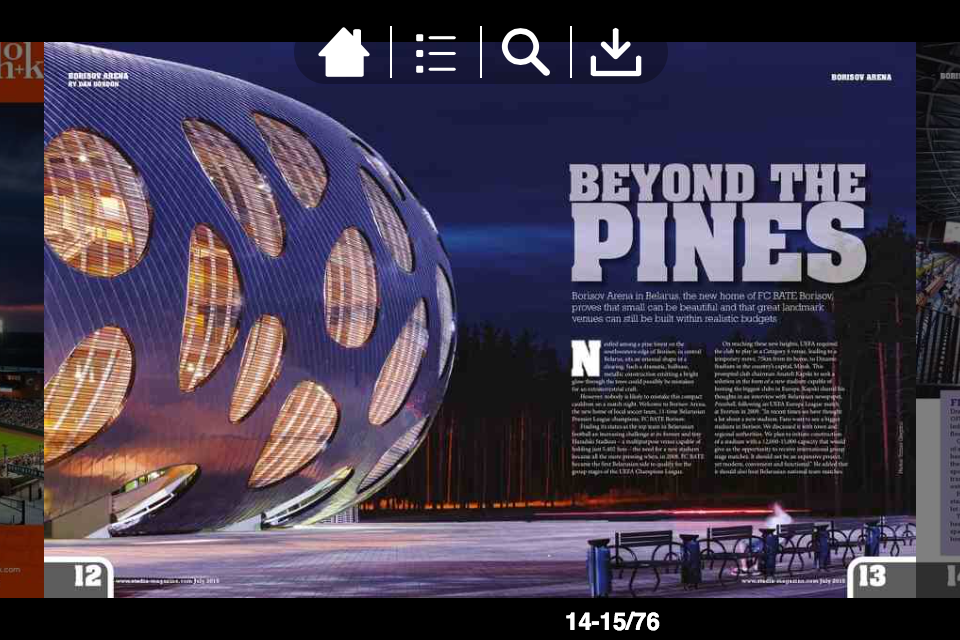

Borisov Arena

Borisov Arena